Can TV Save India?

24.12.2014

L.A. Weekly, 05 ноября 2014 г.

Can TV Save India?

As a teenager in Bombay, Aamir Khan was a tennis champion. When he came home from a match, his mother would ask if he'd won. Usually the answer was yes. She'd give him a hug.

After five or 10 minutes, though, she'd come back and sit next to him. She'd say, "The boy who lost to you, he must have reached home now as well. And his mom must have asked him the same question. And he would have told his mom that he lost." What is his mom feeling, he wondered?

The first time it happened, Khan thought: Did I do something wrong? Should I have lost? But over time, Khan started to look at his opponent differently. He would still try to win. He just would try to connect with him, somehow.

Decades later, Khan is watching a video to prepare for an episode of his first talk show, Satyamev Jayate. A woman has been gang-raped, and the rapists later tracked her down and burned her. On her hospital bed, she speaks her dying words.

Khan covers his eyes and watches through his fingers. The clip is too devastating to show his viewers.

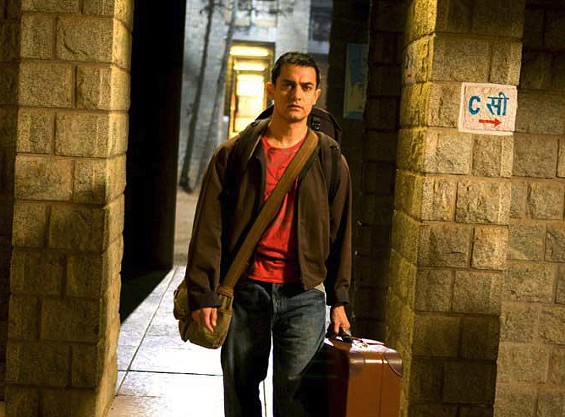

Aamir Khan in Satyamev Jayate (Truth Alone Prevails)

When Khan listens to someone's problems, he imagines himself in her place. "I go through the emotions of fear, anger, frustration, helplessness that she might have felt," he says. He's sitting in the same lounge in his office where he first saw that video, on the sixth floor of a building in Bandra overlooking the Arabian Sea (he and his family live two floors up).

Khan, one of the biggest film stars in India, grew up in this cosmopolitan Mumbai suburb. It would seem dingy and chaotic to American eyes, but amidst stalls selling knockoff accessories and cows in the streets are pockets of upscale hipness: a co–working space, a cafe serving chocolates and churros, boutiques featured in the New York Times. Khan's building, with its gray stone facade and wood trim, is conspicuously posh, even if the balconies have spots of black grime.

Khan's drinking a Diet Coke, wearing torn jeans and a beige button-down rolled up to his biceps. After letting his body go during Satyamev Jayate, he's been hitting the gym while filming his next movie, PK.

For Khan, hosting Satyamev Jayate was an unprecedented move — as if Tom Cruise one day decided to become Oprah. At first glance, he seems to have something of a saint complex. The show's opening depicts him walking along a beach, thinking about how he can solve India's problems. In many films, his character is a too-good-to-be-true savior.

But his motives seem genuine. And when he started conceiving the show a few years ago, the problems around him — the treatment of women, the corruption, the disparity between rich and poor — had become tough to ignore.

For India, these problems came to a head on Dec. 16, 2012, when a 23-year-old woman and her male friend went to a Delhi mall to see Life of Pi. The woman was a med student with dreams of becoming a doctor to the needy.

After the movie, the pair couldn't get an auto rickshaw, one of India's ubiquitous three-wheeled taxis, so they boarded a bus instead. There, a group of men knocked the friend unconscious and raped the med student, before leaving both on the street. The woman died two weeks later. The men were convicted in September 2013.

The crime became an international story not only because of its brutality but also because the woman did everything considered "right" — traveling on public transportation with a male friend. As protests broke out, the public gave the still-unnamed victim a pseudonym: Nirbhaya, "the fearless one."

The incident prompted a nationwide discussion about not only sexual assault but also a host of crimes against women that may seem shocking to Westerners, from acid attacks to female foeticide, the aborting of a fetus because it's a girl. For instance, last year the government recorded 8,083 dowry deaths, in which the husband's family kills the bride or torments her into committing suicide because they're not satisfied with the payment offered by her family.

Government statistics say that incidents of rape have increased steadily in the last few decades, and jumped 35.2 percent in 2013, as the 2012 incident prompted more women to come forward. But the court system botches many prosecutions. The cases last for years, forcing victims to relive attacks over and over, which Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the Population Foundation of India, calls "mental rape. The judges are so insensitive, the police are so insensitive, the lawyers are so insensitive."

More than 95,000 rape cases were awaiting trial at the beginning of 2011, the New York Times reported, and only 16 percent of them had been resolved a year later. During the same year, 26 percent of tried rape cases resulted in convictions, about half of the U.S. figure.

In L.A., lots of TV creators do charity work, but it's usually separate from their day jobs. In India, many in TV feel an obligation to make the medium itself a force for social justice.

The concern then becomes: How do you get people to listen?

"That's been the burden of media, that it should do this pedagogical mission and it has this ability to transform, ability to usher people into modernity," says Tejaswini Ganti, an associate professor of anthropology at New York University, who's an expert on Indian entertainment. "Do people actually change their minds just because they saw something? That's the million-dollar question."

The cliche of India as a country of extremes also applies to entertainment. Some of it has a deep sense of social justice. Some is sexist fluff that's blamed for society's ills.

Back in the 1950s, '60s and '70s, many socially conscious films addressed divides between rich and poor, Hindu and Muslim, frequently through Romeo and Juliet situations in which characters fell in love with the wrong person.

But in the 1980s, things changed. Gratuitous rape scenes became common. "There were a lot of openly misogynistic films, now in hindsight seen as a backlash to various feminist movements that had been going on in the country, against rape, against dowry," says Nandini Ramnath, a film critic who worked for Time Out Mumbai and is now at the website Scroll.

One 2003 study asked street boys in Bangalore to pick the most pleasurable of 26 forms of sexual activity. No. 1 was consensual sex. No. 2 was rape. "When asked how they knew that rape was pleasurable, they replied that men in movies seemed to enjoy it," the study reports.

But the Nirbhaya incident has been a wake-up call. "There was a lot of media soul-searching about the role of the entertainment industry in terms of the sexualized images of women it circulates," Ganti says.

The industry reacted, and today, female power is all the rage. In early September, Mumbai was plastered with posters for Mardaani, about a badass female cop tracking down a human trafficking ring, and Mary Kom, a biopic about an Indian Olympic boxer. Actress Kalki Koechlin was performing a Vogue-sponsored solo show on "womanhood" at Mumbai's main comedy club. The top-rated TV show, Diya Aur Baati Hum, is about a female cop.

More Indian films are depicting empowered women as protagonists, such as Mary Kom, a biopic an Indian boxer.

A viral video that has raced past 6 million views shows Bollywood's Alia Bhatt working out at "Dumb Belle Mental Gym," spoofing the perception that she's just another dumb actress, which caught hold after a talk show appearance in which she seemed not to know the name of India's president. "If a man says something like that, no one gives a shit," says Rohan Joshi of the comedy group All India Bakchod, which created the video. "If a woman says that, it's 'Look at the dumb blonde.'?" Bhatt was owning the moment.

Even advertising has become a source of empowerment. A commercial for the jewelry company Tanishq from 2013 portrays a woman getting ready for her wedding, and then in walks a child, her child, implying that it is a second marriage.

India churns out films with macho action stars, but in the last few years it's made room for more female protagonists. A big step forward was the dramedy Queen, released in March, about a woman whose fiancee leaves her right before their wedding. She defies her family by taking her honeymoon anyway, to Paris and Amsterdam (where she lives in a hostel — with boys as roommates).

"It was so refreshing to see a mainstream Bollywood movie featuring a mainstream Bollywood actress where the narrative was flipped — a woman taking her own life into her own hands, defying her family's decisions, blah, blah, blah, and going on an independent journey, which is so unheard of," says Rega Jha, editor of Buzzfeed India. "This was a woman from a small town. She wasn't a South Mumbai rich girl going on vacation by herself. She was a rural girl with broken English."

Queen, which came out in March, is about a woman whose fiancée leaves

her right before their wedding, so she takes her honeymoon anyway.

The poster child for merging mainstream filmmaking with social concerns is Aamir Khan. He learned the business from his producer father, who would have writers pitch their ideas to him on Sundays so young Aamir could listen in and give feedback.

His empathy, which he learned from his mother, became an asset in acting. "Being someone who is emotionally more tuned to what people are feeling certainly helps you as an actor," he says. "When you read a script, you can also go through what a character feels in a much more layered way."

Khan had a high school friend named Satyajit Bhatkal. Bhatkal used to get top grades, while Khan was average, though Khan would still beat him in chess.

Bhatkal went on to study law and become a social activist, fighting for the rights of slum dwellers, writing in left-wing journals that "nobody but 3 1/2 people read, and I was one of them," Khan says.

As Khan became a rising star, he would meet up with his old friend every so often. This guy is giving up his whole life for people he doesn't know, Khan would think. What am I doing?

Eventually, his films started to change. Khan insists he doesn't pick his films for the message; he picks what moves him. Yet there's a common theme.

In 2006's Rang De Basanti, he starred as one of a group of students filming a reenactment of a story about Indian freedom fighters, which galvanizes the students politically. The film struck a chord with bloggers and young activists protesting corruption, and its candlelight vigil in New Delhi's India Gate has become a model for protests.

Khan also directed Taare Zameen Par, about a child with dyslexia, a misunderstood condition in India, and starred as the teacher who lends a sympathetic ear. "Many parents have commented and told me that you know after watching the film, my relationship with my child changed," he says. "The film is not about dyslexia, the film is about child care," and not penalizing people because of their weaknesses.

Taare Zameen Par

But his most successful melding of cause and cash came in 2009's 3 Idiots. He played a rebellious student at a top engineering college, who encourages his friends to think beyond their preconceptions of what life has to offer.

"It exposed the fallacies in Indian education, parents who want their kids to be engineers or doctors at the expense of pursuing their dreams," says Laya Maheshwari, a Mumbai film critic who has written for the Guardian and L.A. Review of Books.

3 Idiots became the top-grossing movie in India's history (it's been surpassed by Khan's more escapist 2013 film Dhoom 3). The film led Khan to Uday Shankar, the CEO of India's biggest television network, who would hire him to create his talk show.

While movies with stars like Aamir Khan are the pride of Indian entertainment, it's television, a relatively new industry in India, that might have even more of an influence.

Ekta Jha, age 12, stands in a narrow alley, wearing a long, traditional Indian blouse, maroon with dull green stripes, over stonewashed blue jeans. Next to her is a rusting metal staircase leading up her family's home — a one-room apartment, where she sleeps on the floor alongside her brother and parents (her dad is a priest). Next door, several men are packed into a room making tiny black windshield-wiper parts.

Ekta lives in Annawadi, a slum near Mumbai's airport, immortalized in Katherine Boo's Behind the Beautiful Forevers. There is running water, courtesy of pipes that snake through alleyways, but no bathroom — Annawadi residents share communal toilets.

On a shelf is a small television, covered in plastic to protect against dust. It's not uncommon in Annawadi but not ubiquitous, either — friends often watch TV with their neighbors.

Ekta especially likes Ek Mutthi Aasmaan, a soap opera, or "serial," about two mothers: one rich, one poor, each with a daughter. The poor one looks after the rich one's daughter — and encourages her own daughter to become something other than a housemaid.

If her mother tries to change the channel to a more traditional soap, Ekta complains. "You watch serials where there is either fighting or there is love," she'll say. "Can we watch something else?"

"I get irritated with those shows," Ekta says, through a translator.

Ekta's friend mentions she likes the more traditional Meri Aashiqui Tum Se Hi, about a guy-girl romance. Ekta dismisses it as silly. "All the show is is her hair flinging in the air," she says.

"I liked it anyway," her friend says. "If she's crying, if she's low, he goes to her and makes her stop crying."

Ekta Jha, 12, and her mother, in the Annawadi area of Mumbai. Jha manages to fit

in television watching despite after-school computer and English classes.

A few miles south, in Dharavi, one of the largest slums in the world, lives Siddharth, a chubby 14-year-old in a bright orange T-shirt. He watches Sony TV's Crime Patrol, which reenacts real-life stories of cops hunting down criminals.

Siddharth was especially moved by the Delhi rape episode. The woman is "in a bad state after and still tells the names of the people who did it," he says through a translator. He thinks of the cops as taking bribes — but he won't when he becomes a cop, he says.

Indian television may seem primitive to American eyes. There aren't many shows with shades of gray. Instead there are soap operas, crime shows, cricket matches and game shows like Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

Color television didn't arrive until 1982. For a while, the only channel was the state-run Doordarshan, India's equivalent to the BBC.

But in the 1990s, cable television arrived and private channels like Star Plus and Zee TV popped up — and quickly started catering to the lowest common denominator. The number of channels grew, without the talent to fill the airtime.

"The last 15 years of television in India had become a total mess," Vinta Nanda, managing director of the Asian Center for Entertainment Education, says. In many popular soaps, "Women were all within the household and they didn't go out and do any work, and they just sat bejeweled, dressed from morning to night."

Nanda even argues that they hindered the country's development. Old values had eroded, but on television, "Those value systems were reinstated, re-imbedded, re-underlined all over again, and it really confused people, because people were growing progressively and suddenly seeing that what they are watching is unchanged, so where do I stand?"

Nanda's organization is not only advising shows on scientific accuracy but it is also pitching new shows to networks. It has a partnership with USC's Hollywood, Health & Society, which advises U.S. shows such as Homeland and Grey's Anatomy.

A former TV writer who wrote and produced at least 16 soaps, Nanda experienced the annoyance of having to fill that airtime, at one point writing 70 episodes of a legal drama about divorce while knowing little about law. She's now encouraging more accuracy, higher quality and shows that relate to viewers' real lives.

"People who are creating are poles apart from the people who are watching, and I just felt there was a huge need to create that bridge," she says. "It's a big struggle within yourself that you can't create what you want to watch. That's a lot of creativity that gets wasted."

Slowly, television has been turning a corner, she says. A good example is the show Balika Vadhu, which has been running since 2008, and follows two children who get married, and later divorce. Forty-six percent of married women in South Asia ages 20 to 24 were married before age 18, according to a UNICEF report — often to escape their families' desperate economic conditions.

Balika Vadhu can't straight out say that child marriage is bad — it has to be delicate about it. But it "shows you through the drama how much better life would have been had these children had a choice to be educated, to grow up and then make choices," Nanda says.

On the set of the soap opera Diya Aur Baati Hum

The popular soap Diya Aur Baati Hum is shot in a studio lot in the northern Mumbai suburbs, where most of the city's filming takes place. The address, like many in India, is denoted by landmarks: "behind Vishnu Mandir, near Thakur Mall, off Western Express Highway..."

On the lot, past the fake police station, through the fake candy shop, there's the enormous fake family living room: high ceilings, lined with cloistered arches painted white, decorated with a green-and-pink floral pattern and twinkly lights.

The director barks into a microphone in Hindi, often during the scene. (The actors' voices are dubbed in later, for better sound quality.) An assistant comes around with trays of tea. Other than that, it's not much different from a U.S. set, boredom included. One guy's playing Candy Crush Saga.

The scene being shot depicts a surprise party for the main couple, Sandhya and Sooraj. When asked what conflict is in this episode, a publicist says there isn't much. It'll air two days later.

The show runs Monday through Saturday at 9 p.m., and 210 million people watch it at least once a week.

Like Balika Vadhu, Diya Aur Baati Hum must walk a fine line between tradition and progress. It has a standard Indian soap opera setup: a woman living with her husband's family, as is the tradition in India, and occasionally clashing with her mother-in-law. Yet in this show, she's training to be a cop.

"In the middle-class families, girls have to struggle a lot if they chose a career which is out of the box," says the actress who plays Sandhya, Deepika Singh, dressed in a blindingly bright-red sari with gold trim. "So many teenagers come to me and say they want to be like me."

Mumbai sophisticates still disparage such soaps as something vapid their mother or aunt might watch. They'd rather watch Breaking Bad.

Uday Shankar, the CEO of Star India, whose channel Star Plus airs Diya Aur Baati Hum, has been trying to change that perception.

Shankar got his start as a journalist, experiencing firsthand the power of media to change minds. While running Star News, one day he found out that the state of Kashmir was preparing an act that said that if a woman in Kashmir married a non-Kashmiri man, she would not be entitled to the family inheritance. Shankar declared that the network would harp on this issue, and pin down every politician they could find for a comment. Within 24 hours, the national government said the bill was unacceptable. It was squashed.

In 2007, when Shankar was promoted to CEO of 21st Century Fox–controlled Star, he brought this outlook to the entertainment side.

"We needed to become the mouthpiece for people's aspirations and whatever people didn't like, whatever people thought needed to change, we needed to start sort of sensing that," he says from his 37th-floor office.

Shankar's floor-to-ceiling windows look out on the towers of Lower Parel, an area in Mumbai where textile mills have given way to hotels, fashionable offices and nightlife spots like the Barking Deer, "Mumbai's first microbrewery." The building's lobby is like a sci-fi waiting room — blue neon lighting, white chairs that look like glowing rose petals, and stars on the ceiling.

Shankar pushed his writers to shake up standard formulas and create more complex female protagonists. They told him it wouldn't work. He told them not to worry — just try it, and he'd foot the bill.

Diya Aur Baati Hum is a resulting success story. Shankar acknowledges that the familiar premise of a intra-familial tension is intended to grab viewers. But progress has to be gradual.

Courtesy of Star India Uday Shankar

"You're not walking out of a marriage, you're not fighting with your in-laws, because when a woman achieves her dream without destroying something, I think that's the enormously positive side of that show," he says.

Several floors down from Shankar is Ajit Thakur, who works in an interior office looking out on rows of cubicles. He worked in New York City as a brand manager for Dove, and Khan's film Rang De Basanti inspired him to switch to entertainment. He now runs programming for the Star-controlled channels Life OK and Channel V.

Both are exploding with programs aimed to teach, as well as entertain. Channel V, aimed at teens, airs Gumrah, which depicts crimes committed by young people, so that viewers can see their root causes.

One show on Life OK, Dil Se Di Dua... Saubhagyavati Bhava?, centered on a woman who marries a rich, good-looking man who turns out to be a wife beater. "We show the torture in all its reality, from beating to marital rape to?...?unleashing cockroaches," Thakur says.

Not everyone responded well to the show, which ran from 2011 to 2013. A group called the Indian Husbands Association threatened a lawsuit. The network also asked viewers what the wife should do, and while 50 percent said she should leave and 15 percent said she should fight back, 35 percent said to wait it out. "The reason why this doesn't get reported is because women think that it's a part of my life I'll accept it, someday he will change," Thakur says. The show had her leave.

The series Laut Aao Trisha even had a subplot in which a man cheats on his wife with another man — one of a small but growing number of gay storylines on Indian TV. But audience members complained that it made them uncomfortable, and Thakur says the show may phase it out since it's not central to the story.

Dressing up television as educational sometimes seems like more of a marketing ploy than altruism. But soap operas have a history of changing hearts and minds.

The pioneer of educational soaps is the Mexican television creator Miguel Sabido, who in the 1970s developed the "Sabido Method." Its signature is a "transitional" character who has negative and positive role models and evolves from the side of the former to that of the latter, demonstrating how audience members can change their own lives.

In 1983, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi invited Sabido to create Hum Log, India's first serial, which Indians still view with nostalgia. The method spread to 100 other countries, most famously to South Africa's soap Soul City.

Arvind Singhal, a professor of communication at the University of Texas-El Paso, who has consulted for Indian series, says that entertainment can make people more comfortable talking about difficult topics. "It's not about how you feel [about an issue] but about how you feel about a character you love or hate," he says. "Then those discussion can lead to actions."

It's tough to establish a causal relationship between television and improved lives. Studies have to control for a number of variables. Does educational TV help a village progress, or does progress bring educational TV?

But some evidence shows that soap operas make a difference. One study found that between 2001 and 2003, in certain Indian villages that got cable television, women were more likely to go to the market without their husbands' permission and less likely to want a son rather than a daughter, as compared to their TV-free counterparts.

Singhal says that specifics from a show can be tracked in the real world. For instance, a storyline of Taru, a radio soap he worked on, focused on a specific form of discrimination: neglecting girls' birthdays. In one episode of the series, a boy celebrates his birthday, and a young girl wonders why she doesn't get the same treatment. Another character decides to make it happen. Singhal later discovered villagers inspired by the show hosting girls' birthday parties.

He now consults on a new soap called Main Kuch Bhi Kar Sakti Hoon (I, a Woman, Can Achieve Anything) which tells the story of a young female doctor who returns to her family's village and helps modernize its health system.

The show's funding comes from DFID, which is the U.K.'s version of the international development org USAID. It's free to the state-owned network, Doordarshan, which, in turn, gives the show free airtime. The government health ministry sends 600,000 text messages every Friday to locals who mobilize around health issues, to remind them to encourage people to watch.

The show uses what Singhal calls "positive deviance" — adapting real-life stories of people who found success deviating from norms. For instance, in searching for couples with relatively few kids, researchers found a woman who has "yes yes days," when she goes out of her way to please her husband, and "no no days," when she's likely to conceive. On "no no days" she tells her husband that she's fasting for his good health — which in the Indian mindset means that she should be respected, and the husband should stay away. The show used an adapted version of this story.

"In our families we don't discuss sex," says the show's creator, Feroz Abbas Khan. "In this serial a lot of things are spoken really very directly, which people haven't done before. So that private conversation coming in a public space that people can actually access itself is a huge thing."

Aamir Khan in 2009's 3 Idiots, which satirized India's education system.

Shankar, the CEO of Star India, remembers walking to see Aamir Khan's film 3 Idiots with his family at Nariman Point, a neighborhood of apartment and office towers along the water. On the way back, his teenage daughter told him that the spoof of India's educational system is the kind of thing he should put on television.

He met Khan through a mutual friend and asked him if he'd thought about television. Khan said he didn't want to follow the traditional arc for Bollywood stars on TV, like a game show or a dance show. He wanted to take on society's problems.

He called his activist friend Satyajit Bhatkal, who's now Satyamev Jayate's director, and they worked for a year with a team of people to research and conceive a show. Then they brought their concept to Shankar, who said yes immediately.

But Khan had some conditions. One was that it would be dubbed from Hindi into India's many regional languages, like Tamil, Bengali and Malayalam. It would also be broadcast everywhere on Doordarshan, which for about 30 percent of the country is the only channel.

Khan also wanted it aired on Sunday mornings. He didn't want people flipping between his show and prime-time soaps.

"Am I going to watch some woman who is having affair with her husband's brother," he says, "or am I going to watch female foeticide? It's a fucking no brainer. I don't want to compete with that crap."

The final marketing risk: not telling people what the show was about beforehand — and not announcing any episode topics after that. "If we tell you guys this Sunday I'm going to show you female foeticide, people are going to be, 'Fuck female foeticide, man, I don't want to watch that, [I have] problems in my life,'?" Khan says. "'I'll watch next Sunday. What is next Sunday?' 'Next Sunday, domestic violence.' 'Domestic violence man, I don't want to watch domestic violence.'?"

He knew the show had to tread carefully on tradition. The very TV they're watching on might be part of a dowry. So you can't just come out and say the system is wrong.

They tried to ease audiences into a place where their views could be challenged. For the female foeticide episode, for instance, he says, "The moment I tell you that a lot of women are having problems, they're being forced into abortion by their in-laws, people are, like, 'Yeah we know women are having problems, why are you telling me?' They won't be interested."

Instead, he began with a monologue about something more universal: mothers. We love our mothers. They care for us. They give birth to us. Then the show cuts to Khan interviewing a woman whose husband and in-laws forced her to have six abortions in eight years. "You're not seeing her as a woman with a problem," he says. "She's a mother."

Satyamev Jayate 1. Episode 01. Female Foeticide: Daughters are precious (06.05.2012)

Khan acknowledges the series' similarity to The Oprah Winfrey Show. But he believes he adds more context: Though people think the abortion of girl babies became more popular solely because women are a financial burden, the government actually started the practice, to stem overpopulation. And while people think it's a problem of illiterates in villages, it happens more often in cities (in part, because the affluent can afford the sonograms).

Leading up to the airing of the first episode in 2012, Khan and his team were a wreck. The actor cries easily, but during this period he would tear up for no reason.

Shankar, meanwhile, reached out to his boss, James Murdoch, Rupert's son, to make sure he had support in case the show was a flop.

"The traditional understanding of entertainment did not capture that kind of a program," he says. "It made you introspective, and when you look in the mirror you will feel guilty. It didn't leave you on a laughing or on an emotional high.

He adds, "If you ask me honestly if I was sure it would work — not at all."

Before its premiere episode, no one knew what Satyamev Jayate was about. But when it opened on that discussion of female foeticide, Indians raved on Twitter about how "heart wrenching" and "shockingly raw" it was. One critic said she was "weeping copiously." Accurate ratings are tough to come by, especially when you're on multiple channels, but Star estimates that 517 million people — about 41 percent of the country — saw at least an episode of the show over its first season in 2012.

The show gave politicians license to take positive but unpopular steps. The health minister of the state of Maharashtra, where Mumbai is the capital, cracked down on illegal abortions based on sex selection. In a few years the state has gone from 894 girls born for every 1,000 boys, up to 940.

After an episode on health care, the state of Madhya Pradesh started buying generic medicines, and can now give them to citizens for free. The episode on disability inspired the city of Gwalior to make the whole city accessible, and they're at 95 percent of that goal. Khan met with the chief minister of Rajasthan and convinced him to create a fast-track court to prosecute doctors who commit female foeticide.

Khan's upcoming film

Citizens reacted as well. India's version of Alcoholics Anonymous had received 30,000 total calls in its entire history until an episode on alcohol abuse aired. That day they got 450,000 calls. The show's call for donations led to the creation of Satyamev Jayate Bhavan, a shelter for women and daughters rejected by their families.

In addition to working on the third season, which premiered Oct. 5, Khan has been filming PK, coming in December. He's toyed with his audiences during the marketing stage, keeping a lid on the plot and releasing a mysterious poster that featured his chiseled body naked, a boom box held over his genitals.

The film is expected to take on what many people see as the ur-cause of India's ills: religion. "This one film is as challenging as all the films that I've done till now in the last 25 years," he says.

Some critics thought Satyamev Jayate could hurt his film career. But Khan was never worried.

"It didn't even occur to me," he says. "I was just doing what I feel like doing."

This report was funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation, administered by the International Center for Journalists.

Zachary Pincus-Roth

Комментарии